Obsessive Plane Fettling

I read a facebook thread a while back where a few folk where playfully prodding fun at those who flatten planes on granite surface plates, lap to 3 billion grit etc. The general spirit of the conversation was, “Look at what Chippendale, etc achieved without any of that rubbish”. From reading my various accounts of obsessive tool fondling here, you might think I took this a little personally. Well done, very perceptive!

I started wondering how true was this? Knowing what I know of tool folk, I found it hard to believe that the people who obsess over their tools today had no counterparts in the past. Being the geek that I am, I started googling and hunting, trying to find any accounts of traditional planes being fettled.

These are not easy to find…. Its something I will probably continue to dig into on and off for a long time. Nicholson has pretty much nothing to say on the subject. The same for Roubo. The process of making/fettling planes seems to be effectively undocumented. If anyone out there has a good text I have not found, please share! But I have found a little something that might help, although its far from conclusive.

The first realisation I had was that the exhalted furniture makers of the time period in question almost exclusively worked with wooden bodied planes. So no, they would have had no use for a surface plate and 10,000 grit sandpaper… If you are flattening a wooden plane, why bother? You would probably do it with another plane. Some old accounts would reference that it was important for certain types of plane to be flat. But they would rarely discuss what they meant by that, or how to check it, or how to achieve it.

Finally I found an interesting quote from Charles Holtzappfel’s “Construction, action and aplication of cutting tools”. Ordered myself a copy and waited for it to arrive. Charles was the son of John Jacob Holtzappfel, part of a dynasty of tool makers. This book is volume II of a 5 book series on Turning and Mechanical Manipulation which is over 3000 pages long. Charles had a short if productive life, being born in 1806 and dying in 1847. So what he wrote concerns good practice in the early 1800’s. If you are not familiar with Holtzappfel tools, get googling, you are in for a treat. Holtzapfel ornamental turning engines are mechanical marvels.

So what does he have to say about planes and flattening? Well the relatively short section on planes is full of interesting nuggets. According to Holtzappfel, a jointer plane should be 28 to 30 inches long... meaning he would only consider a stanley no 8. to be a trying or long plane.

He states that “When the iron is required to be very flat, as for the finishing planes, the surface of the oilstone should be kept quite level”. So Holtzapfel recognised the value of a flat iron, and a flat stone. He used oilstones. That does not tell us much, as they have a huge range of possible grits.

Speaking of a trying plane he states. “The sole of a long plane is in a great measure the test of the straightness of the work”. Referring to the work surface he states. “It is however needful to examine its accuracy with a straight edge”.

In a footnote, he describes how to create a straightedge “as straight as possible” by creating 3 and testing them against each other. The human eye can detect a gap of 1/2 a thousandth of an inch. Holtzappfel certainly understood how to create and measure to that level of accuracy.

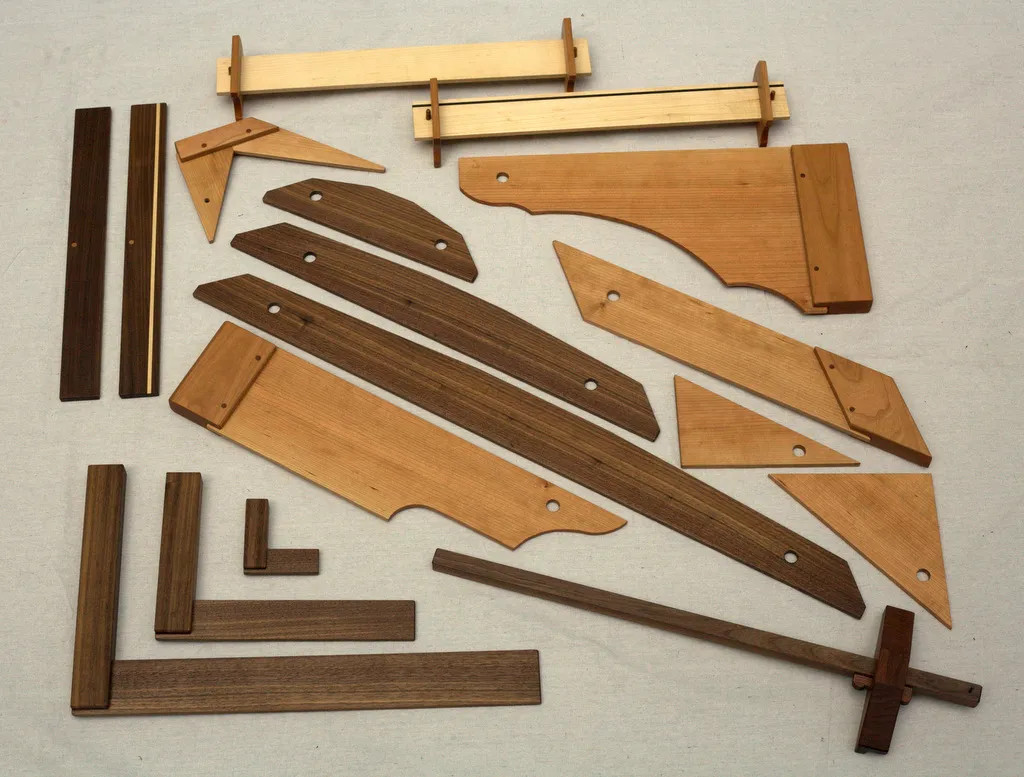

If you read George Walker & Jim Tolpin’s recent book “Euclid’s Door”, they again describe how to true flat surfaces to within 0.0005 of an inch. They use shop made wooden tools to do so.

Does he state that the trying plane should be this flat? No. At best its implied. Does he state that his finished surfaces should let absolutely no light through? No again, its implied but not stated in black and white.

So Holtzapfel in the end does not conclusively answer this question, but I would argue that he strongly indicates the woodworkers in the 1800s certainly had both the tools and the knowledge to flatten their planes more than the average modern woodworker does with fine grits and surface plates, and they certainly understoond the importance of flatness in their tools.

Given the quality of the work they executed, sometimes in challenging timbers. My educated guess is that depending on the plane and the job it performed, these woodworkers probably cared a great deal about the flatness of their planes, and where perfectly capable of flattening them to a degree that exceeds the standards modern plane manufacturers shoot for.

If they where around today, I have no doubt the ocassional surface plate would show up in their shops if they moved to metal soled planes.

A selection of tools from Euclid’s Door a great read if you are interested in how to create your own precision wooden tools.

Holtzappfels Construction, Action and Application of Cutting Tools only has a small part of it dedicated to planes. But it’s dense and rich with good information.

A brand new Lie Nielsen plane is withon 0.0015 of flat, most manufacturers hit 0.003. Thats pretty easy to match on a wooden plane.

The light gap in this article from fine-tools.com is about 0.0015 of an inch (0.04 mm). Its not a big problem for a skilled woodworker to detect and improve on that kind of gap.