Freehand vs Honing Guides

In a little over a week I’m heading over to London for the London International Woodworking Festival, and I’ll be taking Chris Schwarz’s Comb-back stick char class (still a few spots for the build your own saw class if that tickles anyone’s fancy. If you are around on the Saturday say hello. In other news, I doubt I’ll have time to write a distraction for the next two weeks. I’ll be travelling the next two weekends (great time to give it a try if anyone has any ideas in mind).

A long list of recommended tools for the class was sent out. Thanks to building my stools, I had most of them. But quite a few had not seen use for a while. I dug them all out over the last week, and in most cases they needed at least a clean-up and a light sharpen. Some required a complete overhaul.

I went from Chisel, to Scorp to Travisher to Drill bits. Making sure each cut well before packing them for the trip. That put my mind to how I sharpen, and how its changed over time. I had a quick look over the diversion archive and was surprised to find I have never written a post on exactly how I go about sharpen. Something to remedy in a future post.

I started thinking about how I sharpen now, and how its changed over time. The biggest difference I can think of is how much I use a honing guide. I quite like honing guides. I have a fair collection of them. But I rarely use them now.

There are two kinds of sharpening. The kind of sharpening you do when setting a tool up for the first time, and just touching up an edge. They are completely different beasts. Touching up a plane iron takes me less than a minute. Setting one up for the first time may take hours when you take lapping backs and grinding primary bevels into account. New vs vintage tools makes a big difference as well. A brand new blade may be 10 minutes work. A vintage iron in bad shape may take days.

When sharpening a tool for the first time, if it needs a new primary bevel, you need a honing guide, or a grinder. There may be some folk out there who freehand grind a primary bevel, but they are few and far between. Before I had a grinder, The tool went into a honing guide, and then on to 80 grit sandpaper on glass. Then the wonder that is the high speed grinder entered my life. Primary bevels are now ground.

Once that primary is in place I hone a small secondary. For years I did this in a honing guide, but over time that became less and less common. About 5 years ago I took a weekend sharpening class at Rowden Atelier. They encouraged free hand sharpening, taught it, and I got the basics down. Then I went home and continued to use my honing guide.

Over time you start to run into tools that most honing guides cannot handle. A gouge, a drawknife, the freaky cutters on a quirk router. Every now and again you have to get out of your comfort zone and take the tools directly to the stones. Did I mess up? Sure. But other than costing me time to try again. Its usually not the end of the world. You just rethink how you are doing it and then try again until you get it.

I’m not sure when I was in too much of a rush and took one of my chisels free hand to the stone, but slowly I drifted to doing it almost every time. Its not very hard, but does take a little practice. Rock the iron onto the tool until the primary bevel makes contact, which you can feel. Then lift up just a little and pull back. Try and keep the angle consistent. I tend to lock my whole arm and move my body to take the iron back and forth. I’ll typically do that 10 times and then feel for a burr all the way across. Then I strop it and I’m done. I have no dedicated sharpening area/station in my shop. So I grab the stone out of a drawer with a rubber matt, do it on my bench, and then stick them back in their place.

Over time, this tends to take my irons out of perfectly square. If it gets to the point where its a problem. Back to the grinder we go. If I can notice it, but its not a problem. I’ll slowly correct over sharpenings by applying pressure to the high side. Being slightly out of square on most chisels and irons leads to no practical problems in use.

This might seem like I’m making an argument for ditching your honing guides. I’m not. I think both methods are perfectly good. Its a slight trade-off. Time vs accuracy and certainty. For me I prefer to be able to sharpen fast and get back to it. I know a lot of woodworkers whose skills leave me far behind who religiously dig out the honing guide every time. I still like to use a honing guide with very very narrow chisels. There just is not enough reference surface on them to really feel if I’m doing it right. If I want to put a fresh bevel on a skewed iron, that’s really tricky to do on a grinder. I’m likely to break out a honing guide that handles skews and go back to glass and 80 grit.

I have 3 honing guides I keep around. 2 Veritas MKII guides. One with a cambered roller that clamps vertically. If I’m setting up a smoothing plane for the first time, I’ll sometimes use this to put a very slight camber on the iron. That is something I can do freehand, but its not going to be as even.

The second MKII has side clamps and a straight roller. I like that one for very narrow chisels.

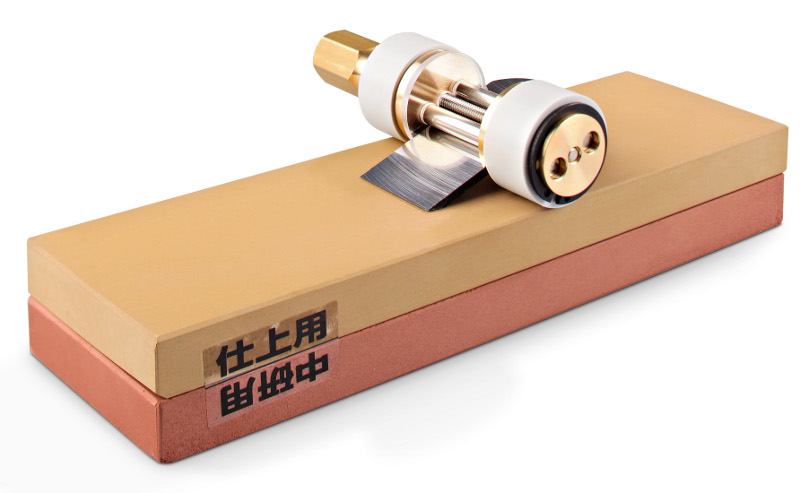

Lastly I keep a Richard Kell No. 1 guide handy. I have some truly tiny spokeshaves around. Its very hard to hold them at a consistent angle freehand, and this little guide is one of the few that will hold the tiny irons steady, while still allowing it to contact the stone.

So I mostly freehand, but I like my honing guides. Where does that leave us? Where it usually does. There can be a lot of snobbery in woodworking. Unplugged vs plugged. Machines vs Hand Tools. Vintage vs New Tools. If it works for you, it works for you. But keep trying new things, and keep learning. If you have never free hand sharpened, maybe grab one of your beater chisels and give it a try. You might be surprised by how quick it can be. If you free hand everything. Grab a honing guide and take one of your worker tools to it. Are you getting a better edge? Might be worth taking the tool back to a guide more often for a reset. Either way, there is little more satisfying in woodworking than taking a fresh sharp edge to wood and watching the shavings fly.

The Veritas MKII guide. Very flexible, as you can change out the head and roller for the right one for the job. Here you can see the vertical clamp above, best for larger irons. And the side clamp below. Best for narrow blades. You can also get a setup jig for handling skew irons.

The Veritas MKII guide. Very flexible, as you can change out the head and roller for the right one for the job. Here you can see the vertical clamp above, best for larger irons. And the side clamp below. Best for narrow blades. You can also get a setup jig for handling skew irons.

Top right you can see the cambered roller than I’m fond of for smoothing plane irons.

Top right you can see the cambered roller than I’m fond of for smoothing plane irons.

The Richard Kell No. 1 Honing guide. Hard to beat for very short irons.

The Richard Kell No. 1 Honing guide. Hard to beat for very short irons.